Palm Sunday

Please download the sermon for Palm Sunday, below

Please download the sermon for Palm Sunday, below

Ezekiel 37: 1014, Romans 8: 6-11, John 111-45

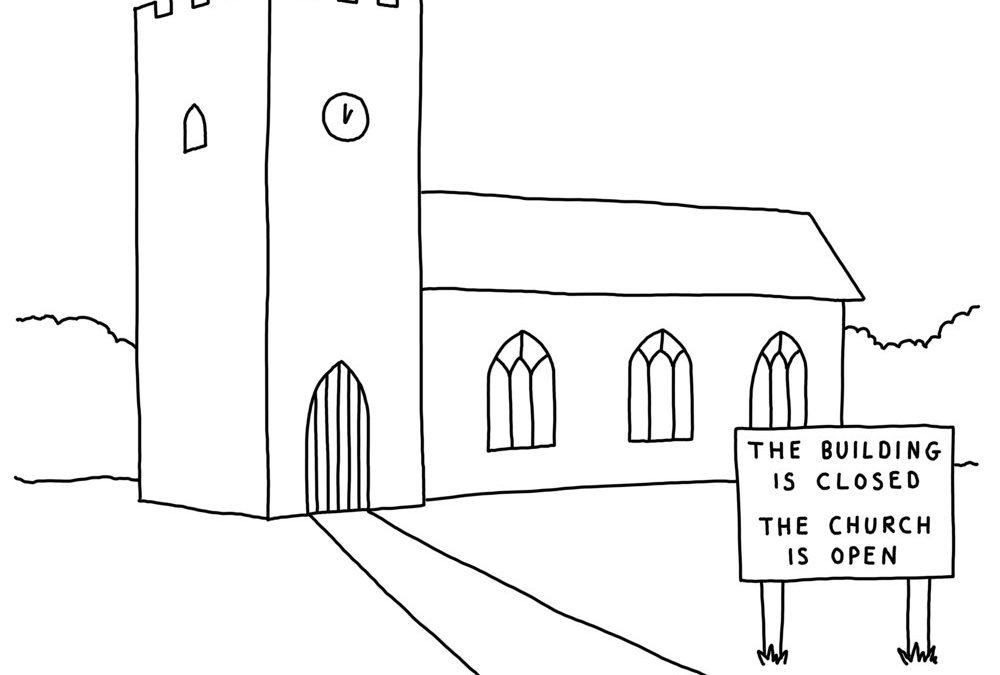

Another Sunday into the Covid 19 crisis, and another cartoon to start this week’s sermon, with thanks to Dave Walker for making this available, free, to all.

I cut the grass yesterday – I wouldn’t dignify it with the soubriquet “lawn”, as it has been permanently shaped by a puppy who dug holes at will and who has created bare earthen pathways across it in her constant pursuit of interloping foxes. It was a totally normal thing to do, to get the lawnmower out and put some order into the garden as Spring starts to burst out around us. And yet it was not a normal day at all. Conversations with people passing by happened at a great distance. Barely any cars could be heard, and the silence in the sky from absent airplanes is still slightly strange, if a little wonderful on the birdsong front.

Everything appears normal, but it isn’t. Our lives are circumscribed by Government advice. Normal human contact has been shrunk. Our homes are more lived in than for many years, now, and there appears to be no end in sight. The churches are locked, bolted up, unavailable. Our normal way of worship has been put on hold. Prayer has become personal and internalised, Bible reading a solitary activity.

But as Dave Walker’s simple but effective cartoon states, the Church is very much open. We continue to worship our God, we continue to rejoice in our Lord and Saviour, Jesus Christ. We are still powered by the Holy Spirit to reach out to others in love and care, to offer of ourselves what we can so that others can enjoy the fulness of life that God offers us in Christ.

Two out of our three readings for this Sunday are downright strange, too. It is not normal to visit a valley full of bones and to see them return to their full human form. It is not normal for Jesus to delay visiting a sick person, so that he dies. It is not normal for Jesus to talk theology with a grieving sister. It is not normal for Jesus to raise his friend Lazarus from death to life. But it is normal for Jesus to weep with Mary, it is normal for Jesus to command life to appear. It is normal for Jesus to cast off from Lazarus the shackles of illness and despair and replace them with joy and wholeness.

In these difficult, abnormal times, let us hold on to the normality that God has created, that Jesus has restored, that the Holy Spirit empowers. God’s amazing, self-giving love brings life and joy, health and hope. Jesus Christ, by his life, death and resurrection, has brought us all back to a normal relationship with our loving God, and has demonstrated how to be fully human. God’s Holy Spirit is in us all the time to guide us in our choices and to alert us to the needs we will encounter and how we can be part of their solution.

Let us, through this abnormal time, explore what being fully human really means. Look at the example of Jesus, and see how he behaves. He gets tired and angry, emotional and joyful. He exposes people’s hidden motivations, both bad and good, and draws them on to a truthful way of living. He understands suffering and anxiety, as he went through both, in extreme circumstances. He knows what it is like to live under circumscribed laws, as the Romans ran Israel during his time, and there were very strict rules on where you could travel, how you could work, and with whom you could associate. The Romans were very good at locking down whole towns or villages, in a way that would make our current restrictions look very lax.

We have a God who understands what we are going through, who knows the human heart and how it reacts to joy and pain. We have a God who loves us through those times, walks with us, supports us and casts off our shackles and leads us into fulness of life.

May God give us grace to use this time to grow as his children, to learn to love in new ways, to care in new ways, to share our joys and sorrows in new ways. And may we have confidence in our loving God, to sustain and protect us all the days of our life, to his eternal praise and glory. Amen

Fr Peter 28.3.2020

As these are particular times, I am starting my sermon with a picture – courtesy of Dave Walker, the regular cartoonist in The Church Times. However we worship and pray together over the coming weeks and months, we start with the recognition that God is with us and binding us together, wherever we are, whatever we are doing, and whatever is going on. Christ’s Church will continue to gather, whether in homes or in church buildings, and Christ’s love will be shown in acts of generosity and care to those who live around us. As for producing a sermon which I know will not be preached, well, that feels a little strange, but hey ho, here we go.

Today will be a difficult Mothering Sunday for many. Some will not be able to travel, to be with their mother on this special day. Others will still be grieving the loss of their mother over this past year. Many of us will be worried about our mothers, especially the more elderly amongst them, as the threat of the Coronavirus develops. Mothering Sunday was traditionally a day of returning home, of sharing family life together for a day, before returning to the routine of work and separation. The world of work and family life has changed immeasurably since those days, and this year’s Mothering Sunday will not be like that for many. Do today’s readings have anything to say to us? Samuel is taught not to look at outward appearances, but to examine the heart with the mind of God. The healing of the man born blind rules out any notion of the transmission of sin and blame from one generation to the next, but after that it is all about seeing Christ for who he truly is, not really about mothers.

So we need to go elsewhere. We have been given Psalm 23 to read together, a psalm of comfort and calm, a psalm which talks of the gentle but wise leading of God. The Psalmist describes how God leads us to safe places, brings refreshment and shelters us from fear and threat. Food and wine are shared, as we move seamlessly through to the eternal presence of God, our shepherd. The usual reading of these verses is to draw a parralel between God as shepherd and God as king, referencing King David, the boy who was taken from being a shepherd to become the king of Israel. But our God is not a tyrant: rather, he is a king who provides for us in all ways, both physical and spiritual, so that we may live in peace in his presence.

However, today is not a normal Sunday, and therefore the normal way of reading Psalm 23 has to go. So I am going to attempt to replace that with approaching Psalm 23 from a mother’s point of view. It can fairly be argued that I am in no position to do this, but I have a mother, I am an observer of mothers, I live with the mother of my children and I have a certain amount of imagination, so bear with me, please.

In this world, there are many mothers who cannot provide for all their children’s needs. Many mothers in our country are choosing between food and heat, their children eating and them going hungry. These mothers’ desire is to see their children happy, warm and fed, but many factors are working against them. Therefore, if God is one who provides fully and lovingly, that is an easy parallel to agree.

How many of us are brought up sharply with our mother’s voice ringing in our ears, “Don’t do that, please” or “You’re not going out dressed like that!” Yes, the moral teaching within the family is a shared function, but whose tones do you remember when that teaching of long ago rises subtly to the surface?

Who tucked you up when you were ill, or afraid, or anxious? Who brought out the blanket, or the tissue, or the story book at times of distress?

I grew up in a family where my mother was the only cook, despite being a head teacher. Things are different now, but who really plans those family feasts or picnics? And who stormed up to the school, outraged at another child’s behaviour towards you, or challenging what appeared to be an unjust decision by your teacher? Ask any teacher how the gender breakdown looks of parents who come into school to complain, and I think I know the answer. To see our mother on the warpath might well have made us cringe as children, but ultimately, she did it for our very best interests.

“Goodness and loving mercy…” what are they but every parent’s desire for their children, and much as we may roll our eyes at our teenagers, the best times are when they come home again and comment that our food tastes better than their attempts at making it, and that our sofa is more welcoming than theirs.

Truly this is a psalm of divine parenthood, which today, Mothering Sunday, puts God right in the centre of the maternal role. The creator God who brought the world into existence, who gave birth to us all, desires nothing more than to tuck us up in the blanket of her love and forgiveness and keep us safe and warm from all that might harm us, especially during this time of crisis.

Keep this psalm close to you as we journey together through these strange times. Acknowledge God’s loving protection as we offer care and comfort to those around us, as best we can. And talk to your loving Mother God, daily, because she wants to hear everything you feel and know, and to share with you in bringing answers to this troubled world. Amen

13th Sunday after Trinity 2019

How re-assured would you feel if I said that I only have three points to make this morning? Would you imagine that we are in for a short or long sermon? Storytelling is full of threes – from the three little pigs to the three bears that Goldilocks encounters, from the three mystery caskets in The Merchant of Venice to the three prophecies by the weird sisters to Macbeth.

All the best stories come in threes, but we this morning only have two. We have the story of the lost sheep, and the story of the lost coin. There is a third to round off the series – the Prodigal Son – and it is not there. Why? Is it a conspiracy, to keep us from figuring out Jesus’s intentions? Or is it sparing us a very long Gospel reading? The third possibility, to stay true to the emerging theme, is that the compilers of the lectionary think we know the story of the Prodigal Son so well that we don’t need to hear it again, and can provide the ending to the sequence all by ourselves. As the twist is always in the third story, we have to decide if that is patronizing or a compliment.

Be that as it may, we have two other readings all about God changing his mind, so in the grand scheme of things, we might just be in a right old mess. Which of course we are, because today we do not know where we are going as a nation, what the impact of what might happen might be to us, to our community, to our country and to the wider world. There has been much talk of absolutism – sticking to a decision that was taken in 2016 – and of alteration – try the referendum vote again and see if people have changed their minds. There are hardliners on both sides, but just in case there are those who would seek to apply God’s standards to this unholy mess, remember the outcome of Moses pleading before God as the Israelites danced round a statue of a golden calf at the foot of Mt Sinai. God, in his holiness, has sworn to destroy the people. Moses pleads for their forgiveness and for God’s own honour in the world, and these astonishing lines follow, “And the Lord changed his mind…”. There: to change one’s mind can be God-like. Yes, it involves mercy and great grace, as the Apostle Paul discovered, but it happens.

So what exactly is Jesus doing in this series of three stories? Look first at his audience. A ragtag group of people surrounds Jesus. Quislings, “sinners” – what on earth does that mean? And some Pharisees and scribes. Poles apart socially, theologically, politically and culturally, this crowd is about as divided as a crowd can be, and just to provide the full panoply of Jewish dissent, there are at least two of Jesus’s disciples who could be described as terrorists. None of these people would normally talk to each other, none of these would normally share each other’s company, but in the presence of Jesus, they are all brought together. They all want to listen to him, to learn from him, receive something from him that is apposite to them, so Jesus skillfully draws them all in.

The lost sheep – a cheerful pastoral story, easily accessible, a simple point made about the repentance necessary from those who have wandered away from the fold of Israel. The Pharisees nod approvingly, the tax collectors & the “sinners” take comfort in the possibility of their redemption. There is grace for those who take it upon themselves to drift away from the orbit of God’s love, and they will always be welcomed back.

The lost coin – same thing, only this time it is hardly the coin’s fault that it has gone missing. But things happen, circumstances can conspire against us – remember that we are all two months’ rent arrears away from homelessness, and four months mortgage arrears away from being out on the street – and we can simply get lost through no particular fault of our own. But, Jesus insists, God will find us and bring us back, and all the angels will have a big celebration. Again, the Pharisees nod, the tax collectors and “sinners” breathe a sigh of relief, and Jesus moves on to the third story.

But wait there. One part of both stories has not been talked about so far – the comment about the 99 safe sheep & the 9 safe coins. Is God not all that concerned about them? Those faithful people who, week by week, live out the life of faith, worship consistently in God’s house, and share his love in practical and meaningful ways day by day – is God not interested in them? The Pharisees are so caught up in the blame game that Jesus is offering that they have not noticed how they are being strung along. They are safe, they think, these Pharisees, they are connected to the divine, so it is only right that God should be doing something special for those who are outside the fold or disconnected from the main body of Israel. Should they not be concerned about their status in these two stories?

They really should, because the Prodigal Son narrative is coming down the tracks, and the whole ending section about the ingratitude and the anger of the son who stayed at home is aimed directly at them and, potentially, at us.

Who are those “tax collectors and sinners” in today’s reality? Or, more practically, our reality? Tax collectors in Jesus’s time were people who had sold out to the occupying force, who had thrown their lot in with the Romans. It doesn’t take much for us to identify people today who we judge to be quislings, in thrall to unthinking or malevolent political or social forces – according to us, that is. And the term “sinners” is just a catch-all word for people of whom we do not approve, who could range from fat cat business people to rough sleepers or anyone else who doesn’t meet our high standards of acceptability. It’s the old “U & non-U” thing – “people like us” – and we can fall into it so easily, especially in today’s divided Britain with “leavers” & “remainers”, snowflakes and baby-boomers, Generation Z & Millenials.

We have to drill it back into our hearts that God is not like that. God’s love is so extraordinary in its length and breadth and height and depth that we dare not slip into Pharisaical ways, or we too will need to be shamed out of our lazy thinking and returned to the fold and the unity of God. We are all both lost and safe, a prodigal and the stay-at home son.

Our final hymn today is “Amazing grace”, a heartfelt acknowledgement from someone who regarded themselves, along with Paul, as “the chief of sinners”, that God could reach out and forgive even someone like him. Having that same mindset will enable us to rejoice in our salvation with the angels, and share in their joy at everyone else’s.

There is a fairly clear set of ideas in this morning’s Gospel: glory and love. Glory, as we all know, means a nice knock down argument, but don’t take my word for it, as that definition comes straight from Humpty Dumpty, who, as we know, can make any word suit his own purpose. Love is a word that is bandied about without much thought for its complexities. So not much help there. The context is the upper room, during the last supper. Jesus is with his disciples, sharing Passover together as they had done many times before, but this time they are in Jerusalem, and, as the text says, Judas has left the company to garner a group of thugs to arrest Jesus and hand him over to the authorities. Judas feels betrayed, and wants to do away with Jesus, to denigrate all that Jesus has said and done, to wipe out any memory of him from Israel. But it is at that moment that Jesus says that he has been glorified – the betrayer is on the loose, torture and death beckon, but Jesus says that he has been glorified by God. How? What we see in Jesus at this moment is humanity at its very best. Betrayal is possibly one of the worst things a human being can do to another, and betrayal to death is appalling, but Jesus, who knows what is afoot, does not run from it, nor ignore it. Instead, he welcomes the worst that humanity can do to him, so that he can do the best that God can do for humanity. Jesus will die so that we can live, and rise again, so that we can have fullness of life. And that is glory. Now, if that is the best that God can do for us, is it any wonder that Jesus should ask of us to do the same? Not for us to find glory, but for us to love one another, in the same way that Jesus has loved us. But this is more than a request – this is a commandment. It follows hard on the heels of another commandment that Jesus gave his disciples – to remember him in bread and wine, which is what we are doing this morning – two new commandments, that take our worship to another place, and our love response to a practical outworking of God’s love in the world. Which is harder? To come here on a Sunday morning and remember Jesus in bread and wine, or to love sacrificially the people who are sat around us this morning, as Jesus loved us,? I would imagine that we would automatically say “remembering Jesus” – we just have to turn up, and the rest is done for us. But to love sacrificially, as Jesus loved us, that is much, much harder. Is it possible to command love? In a human situation, it is probably not – love grows naturally, either within the family or between friends. But Jesus commands us to love one another. Then is it possible to teach love? Is it a function of parents, or godparents, or Junior Church leaders, or – heaven forfend – the vicar? How are we going to do it? The first thing to do is to open our eyes, really to look around us and see people. Not to stare, as that would be rude, but to look and recognize in the other people who fill this space that they are loved by God and redeemed by the risen Christ, and that we all stand together in God’s love in exactly the same way. That is the first step on the road, as Jesus was able to look at everyone he met and see in them a child of God, loved by God and he was therefore able to express the love of God to them in the ways that they needed – healing, teaching, encouragement, rebuke, friendship. And then we talk to all these people, and then we pray for them, and then we find the things that they like and the things that they need, and we share their burdens and grow together in Christ. And then we discover that there are people here that we don’t know, so we talk to them, and share with them, and rejoice with them. And then we discover that there are people we know who are not here, so we invite them along and go through the whole process with them – and that is what Christ means by his new commandment – a process of love that engages with others and includes them, shares freely with them and enjoys their company, whoever they are. And the ones who are difficult to love? (there are always some of them) We persevere, we remember the commandment, we put it into practice. It can be hard work, but Christ commands us to do it, for his sake, and so we must. Loving and remembering, the two practical ways that Christ gave us to build up his people and to change the world. Let’s embrace them this morning, remember Christ in bread and wine, and change the world through his love. Amen

5th Sunday of Easter 2019

There is a fairly clear set of ideas in this morning’s Gospel: glory and love. Glory, as we all know, means a nice knock down argument, but don’t take my word for it, as that definition comes straight from Humpty Dumpty, who, as we know, can make any word suit his own purpose. Love is a word that is bandied about without much thought for its complexities. So not much help there.

The context is the upper room, during the last supper. Jesus is with his disciples, sharing Passover together as they had done many times before, but this time they are in Jerusalem, and, as the text says, Judas has left the company to garner a group of thugs to arrest Jesus and hand him over to the authorities. Judas feels betrayed, and wants to do away with Jesus, to denigrate all that Jesus has said and done, to wipe out any memory of him from Israel. But it is at that moment that Jesus says that he has been glorified – the betrayer is on the loose, torture and death beckon, but Jesus says that he has been glorified by God. How?

What we see in Jesus at this moment is humanity at its very best. Betrayal is possibly one of the worst things a human being can do to another, and betrayal to death is appalling, but Jesus, who knows what is afoot, does not run from it, nor ignore it. Instead, he welcomes the worst that humanity can do to him, so that he can do the best that God can do for humanity. Jesus will die so that we can live, and rise again, so that we can have fullness of life. And that is glory.

Now, if that is the best that God can do for us, is it any wonder that Jesus should ask of us to do the same? Not for us to find glory, but for us to love one another, in the same way that Jesus has loved us. But this is more than a request – this is a commandment. It follows hard on the heels of another commandment that Jesus gave his disciples – to remember him in bread and wine, which is what we are doing this morning – two new commandments, that take our worship to another place, and our love response to a practical outworking of God’s love in the world.

Which is harder? To come here on a Sunday morning and remember Jesus in bread and wine, or to love sacrificially the people who are sat around us this morning, as Jesus loved us,? I would imagine that we would automatically say “remembering Jesus” – we just have to turn up, and the rest is done for us. But to love sacrificially, as Jesus loved us, that is much, much harder.

Is it possible to command love? In a human situation, it is probably not – love grows naturally, either within the family or between friends. But Jesus commands us to love one another. Then is it possible to teach love? Is it a function of parents, or godparents, or Junior Church leaders, or – heaven forfend – the vicar? How are we going to do it?

The first thing to do is to open our eyes, really to look around us and see people. Not to stare, as that would be rude, but to look and recognize in the other people who fill this space that they are loved by God and redeemed by the risen Christ, and that we all stand together in God’s love in exactly the same way. That is the first step on the road, as Jesus was able to look at everyone he met and see in them a child of God, loved by God and he was therefore able to express the love of God to them in the ways that they needed – healing, teaching, encouragement, rebuke, friendship.

And then we talk to all these people, and then we pray for them, and then we find the things that they like and the things that they need, and we share their burdens and grow together in Christ.

And then we discover that there are people here that we don’t know, so we talk to them, and share with them, and rejoice with them.

And then we discover that there are people we know who are not here, so we invite them along and go through the whole process with them – and that is what Christ means by his new commandment – a process of love that engages with others and includes them, shares freely with them and enjoys their company, whoever they are.

And the ones who are difficult to love? (there are always some of them) We persevere, we remember the commandment, we put it into practice. It can be hard work, but Christ commands us to do it, for his sake, and so we must.

Loving and remembering, the two practical ways that Christ gave us to build up his people and to change the world. Let’s embrace them this morning, remember Christ in bread and wine, and change the world through his love. Amen